Compare Providers

Download our outplacement comparison sheet

Request Pricing

Compare our rates to other providers

When it comes to mergers and acquisitions – commonly called M&A – the whole process can be quite confusing and stressful. After all, employees will be wondering if their jobs are in jeopardy and HR has a ton of different tasks ahead of them. To help take some of the stress out of the equation, we’re going to go over the four most common types of mergers found in the corporate world.

First off, what is a merger? What happens when companies come together in the first place? Why would a company want to merger with another one?

Well, there are many reasons for companies to merger, forming a larger, more powerful organization. These reasons are largely what dicates what type of merger the action is labeled as.

“A merger is an agreement that unites two existing companies into one new company,” reports Investopedia.

“Mergers and acquisitions are commonly done to expand a company’s reach, expand into new segments, or gain market share. All of these are done to please shareholders and create value.”

So, though a merger seems like a troubling move for companies on paper, it’s actually a solid business move that both companies will – if done correctly – benefit from.

The weird thing is that mergers are far more complicated than that just two companies deciding to come together. With any sort of a huge business move, there are different categories that mergers can fall into.

Types of Mergers

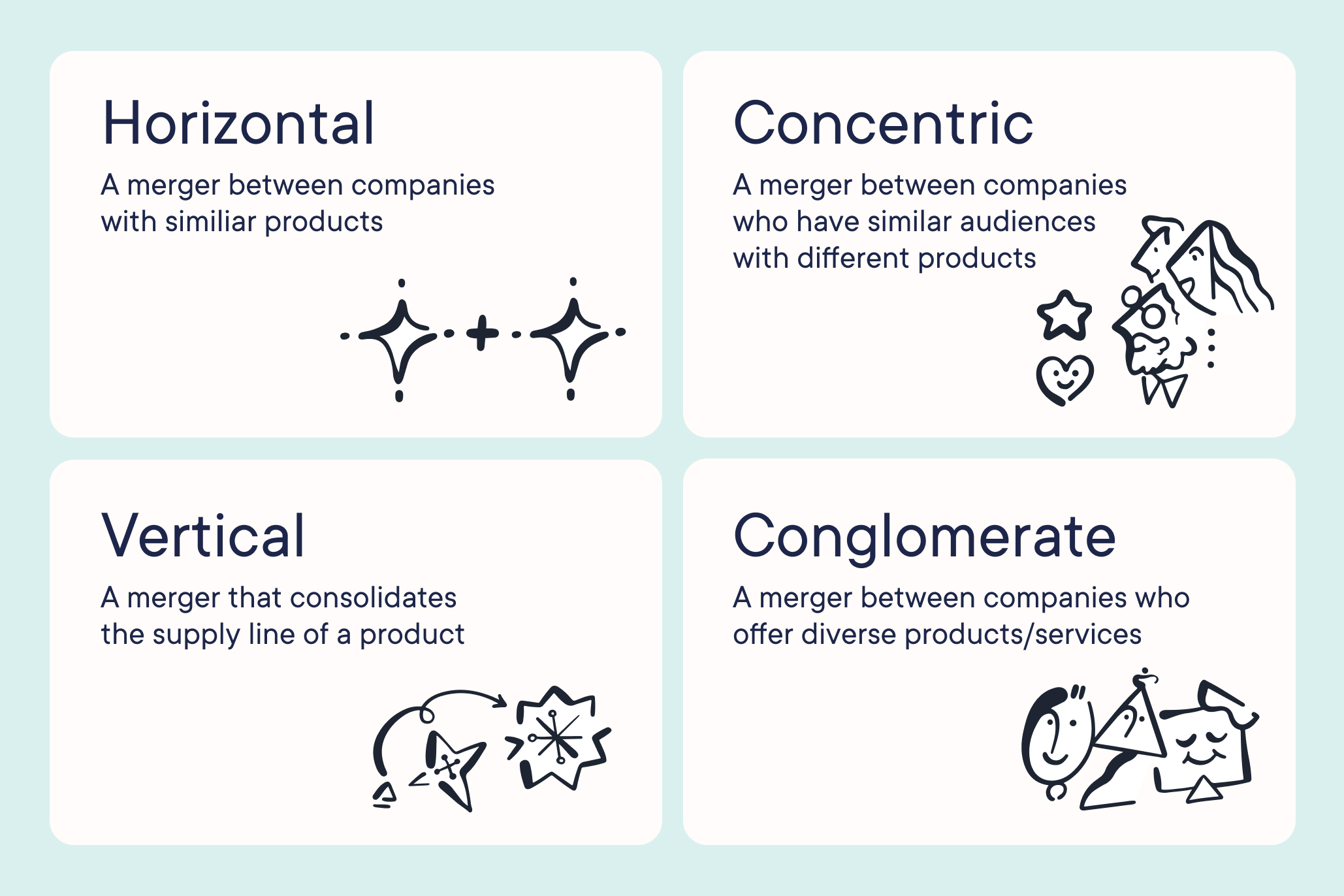

There are typically four types of mergers:

- Horizontal – a merger between companies with similiar products

- Vertical – a merger that consolidates the supply line of a product

- Concentric – a merger between companies who have similar audiences with different products

- Conglomerate – a merger between companies who offer diverse products/services

Let’s dig in a bit to make sure we understand each of these different types of mergers:

The Horizontal Merger

The first type of merger we’re going to look into is ‘horizontal.’

A horizontal merger is when two companies who sell the same product or cater to the same demographic come together to increase their reach. Typically, this type of merger is done between direct competitors.

The best way to think about horizontal mergers is to look at how startup companies get acquired by larger companies either to absorb their technology – which can be used by the larger company to fill a gap they have – or because they are posing a threat and have somehow captured part of the market that the bigger company has been trying to figure out.

It’s important to note, though, that this type of merger must happen between two companies with similar products, customers, and target market. Otherwise, you end up with a completely different type of merger.

The Vertical Merger

Unlike horizontal mergers, vertical ones aim to capture more of the means of production than expanding their market cap by merging with competitors or innovators in their niche.

Basically, a vertical merger is when one company merges with a company that is better at one step of their process.

“An automobile company joining with a parts supplier would be an example of a vertical merger. Such a deal would allow the automobile division to obtain better pricing on parts and have better control over the manufacturing process. The parts division, in turn, would be guaranteed a steady stream of business.”

In other words, if you should own a company that makes shoes, you probably would benefit from merging with a company that makes rubber, or a company that makes fabrics. By doing so, you will be able to make your product for a cheaper price by controlling more of the supply chain, which – in effect – gives you a huge competitive advantage.

The Concentric Merger

Concentric mergers are closely related to horizontal mergers because they both aim to complete the same goal: a larger market cap.

However, concentric mergers happen when a company merges with another company that sells products to the same customers, though they sell different products, making them indirect competitors.

“The companies involved in a congeneric merger are typically engaged in complementary, not directly competitive activities,” explains Natasha Gilani from Bizfluent.

“The companies involved in a congeneric merger are typically engaged in complementary, not directly competitive activities.”

Here’s an example:

Say company A sells printers for home offices. It makes complete sense for them to then merger with a company that produces ink or paper. Not only are the same customers buying all of their products, they are buying at the same exact time. So if the bigger printer company owns the paper company and the ink company, all of the companies involved should benefit from coming together.

The Conglomerate Merger

The final common type of merger is when two or more companies come together who do not compete at all. This usually happens with giant companies that work in many different areas of expertise.

Think of some of the biggest companies working today. Your General Electrics, Disney’s, etc.

GE is a great example, according to Point Park University, because they work in tons of different areas from aviation to healthcare to household products to various gizmos. GE seemingly does it all and they were able to pull that off by acquiring other companies that specialized in these fields.

But what would make a company want to start working in so many different areas? After all, that seems to be a challenge – and it is.

“There are several reasons as to why a company may go for a conglomerate merger. Among the more common reasons are adding to the share of the market that is owned by the company and indulging in cross selling,” reports Economy Watch.

“The companies also look to add to their overall synergy and productivity by adopting the method of conglomerate mergers.”

This type of merger is definitely harder to pull off and sometimes does fail spectacularly. However, the companies that can and do pull them off become juggernauts of industry.

What Do All These Types of Mergers Have in Common?

Given that there are so many different types of mergers and acquisitions out there, it makes sense that there are laws out there that govern what companies can and cannot do. This is largely because big mergers have the power to impact the overall market, possibly leading to monopolies and other things that are bad for business.

There are three major antitrust laws that dictate how mergers can go down. Here’s what the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has to say:

“Congress passed the first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, in 1890 as a “comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade.” In 1914, Congress passed two additional antitrust laws: the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the FTC, and the Clayton Act. With some revisions, these are the three core federal antitrust laws still in effect today.”

Going into every one of these laws and what they impact is for another article entirely. However, if you’re curious, you can read all about these various laws on the FTC’s site here.

Want to learn more about the different types of mergers? Check out our mergers & acquisitions guide here:

In need of outplacement assistance?

At Careerminds, we care about people first. That’s why we offer personalized talent management solutions for every level at lower costs, globally.